Ralph Ellison: A Biography

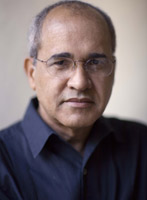

ARNOLD RAMPERSAD

|

|

Visit this book's Amazon.com page >>

| Book Description |

| The definitive biography of one of the most important American writers and cultural intellectuals of the twentieth century—Ralph Ellison, author of the masterpiece Invisible Man. In 1953, Ellison's explosive story of an innocent young black man's often surreal search for truth and his identity won him the National Book Award for fiction and catapulted him to national prominence. Ellison went on to earn many other honors, including two presidential medals and election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, but his failure to publish a second novel, despite years of striving, haunted him for the rest of his life. Now, as the first scholar given complete access to Ellison's papers, Arnold Rampersad has written not only a reliable account of the main events of Ellison's life but also a complex, authoritative portrait of an unusual artist and human being. Born poor and soon fatherless in 1913, Ralph struggled both to belong to and to escape from the world of his childhood. We learn here about his sometimes happy, sometimes harrowing years growing up in Oklahoma City and attending Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Arriving in New York in 1936, he became a political radical before finally embracing the cosmopolitan intellectualism that would characterize his dazzling cultural essays, his eloquent interviews, and his historic novel. The second half of his long life brought both widespread critical acclaim and bitter disputes with many opponents, including black cultural nationalists outraged by what they saw as his elitism and misguided pride in his American citizenship. This biography describes a man of magnetic personality who counted Saul Bellow, Langston Hughes, Robert Penn Warren, Richard Wright, Richard Wilbur, Albert Murray, and John Cheever among his closest friends; a man both admired and reviled, whose life and art were shaped mainly by his unyielding desire to produce magnificent art and by his resilient faith in the moral and cultural strength of America. A magisterial biography of Ralph Waldo Ellison—a revelation of the man, the writer, and his times. |

| Amazon.com Review |

| On the strength of just one novel, as well as a series of lasting essays in cultural criticism, Ralph Ellison stands as one of the major literary figures of the last century. The novel, of course, is Invisible Man, and much of the drama of Ellison's life, as told by Arnold Rampersad in the first major biography of Ellison, is twofold: how Ellison came to write his masterwork, and how he failed to write another. Given complete access to Ellison's papers, Rampersad tells the story of Ellison's long apprenticeship as a musician and writer and his long life, full of honors and frustrations, after the great success of Invisible Man, capturing the complexities, to use of one of Ellison's favorite words, of his elusive subject, at once passionate and patrician, fiercely critical of his country's racial divisions and stubbornly hopeful about its democratic possibilities. Questions for Arnold Rampersad One of the leading scholars of African American literature and the author of major biographies of Langston Hughes and Jackie Robinson, Arnold Rampersad is an ideal biographer for one of the great figures of 20th-century American writing. We asked him a few questions about Ralph Ellison. Amazon.com: Ralph Ellison came from Oklahoma--the "Territory," as he liked to call it--and in his essays he wrote evocatively of the conditions there that nurtured his creative life (although he rarely returned as an adult). What was Oklahoma like for an ambitious but poor young African American like him?

Later overlooking the slights and snubs he experienced as a youth, and dwelling especially on his various friendships with fellow students at the local "colored" schools, Ellison cherished his memory of Oklahoma as a region of almost mythic proportion and magical charm. He took immense pleasure in going back home--but he went home only after he had become famous and could command the respect and attention he had craved in his bittersweet youth. Amazon.com: Ellison spent a long and varied creative apprenticeship before writing Invisible Man. What did he learn along the way that allowed him to make such a stunning debut? Rampersad: Ellison's many years of training as a musician (on the trumpet) as a youth served him in good stead when he committed himself (influenced first by his friends Langston Hughes and Richard Wright) around 1937 to become a writer. He was then 24 years old--pretty late as a start for most important fiction writers, but not too late for a man of enormous drive, wide reading, and restless intelligence. As Ellison served his apprenticeship, he kept his major literary masters close at hand. They were Dostoyevsky for his distillation of the turbulence, vitality, and tragic gloom of Russia in the 19th century; Hemingway for his terse, virile elegance; Richard Wright (although the competitive Ellison would play down his influence) for the gritty American realism that sought to expose and redress American social injustice; Andre Malraux, for combining in an often breathtaking way the life of radical action and the life of the mind; and in some ways above all, T.S. Eliot, whose landmark poem of 1922 The Waste Land encouraged Ellison in his mature commitment to modernism, a pervasive if mild surrealism, jazzy improvisation, and cosmopolitan learning. Ellison was a sometimes crudely Marxist writer until about 1942, when he began a zealous conversion away from the literary and political left. Three years later, he started Invisible Man. By that time, after years of hard work as a reader and a consciously apprentice writer, he was fully committed to an esthetic based in liberal humanism, with a particular passion for explorations of American literature and culture. Amazon.com: The great question with Ellison is, of course, what happened after Invisible Man? Why do you think he struggled so with his second novel? Rampersad: In some ways, the winning of the National Book Award in 1953 for Invisible Man, and not the mere publication of the novel itself, transformed Ellison's life for better and for worse. This prominent award to a young black man (who beat out Hemingway for the prize) set in motion a flood of honors, big responsibilities, and financial rewards. These tokens of professional success steadily combined with Ellison's proud perfectionism to make it increasingly hard for him to offer the world anything less than a work conceived and executed on a scale that reached grand--perhaps impossibly grand--heights of excellence. Committed to a literature of myth, symbol, and surrealism, instead of the literature of everyday life, he found himself often entangled in fiction writing that drew on techniques borrowed from James Joyce and on Faulknerian myths and fables about race, miscegenation, social injustice, and American culture. He also prized improvisation, which called for powers of organization and discipline that proved finally to be beyond him as a novelist. And he was not helped by his principled refusal to allow himself to be comfortable with the many African Americans who were attracted, starting in the 1960s, by black cultural nationalism and black power. Although he believed in African American culture, he became increasingly and painfully isolated in ways that led him away from the completion of vivid fiction set largely in that culture. He liked to blame his writing problems on the fire in 1967 that destroyed his country home in Massachusetts, but the facts about the fire do not support this claim. Amazon.com: You've written major biographies of Langston Hughes and Jackie Robinson as well. How did Ellison's public path through the mid-century compare to theirs? Rampersad: Langston Hughes was the polar opposite of Ralph Ellison in many ways. Hughes loved the masses of black Americans unconditionally; he believed in world travel and in varieties of friendship that covered almost the entire social spectrum; he was almost compulsive in his desire to help younger artists, especially younger black artists; he wrote consistently in a variety of forms of which poetry, drama, and fiction were only the most conspicuous; he also cared little for esoteric art and Olympian esthetic standards. Ellison was a different man. He traveled little; guarded his resources zealously and believed that young writers should make their way by their individual efforts as he believed he had done for himself; he didn't hesitate to criticize black leaders when he thought they were abusing their authority, which was often, as far as he was concerned; and he set the highest esthetic standards for himself and others. He stuck to writing fiction and essays, and his total output is dwarfed by that of Langston Hughes--except, Ellison would say proudly, in terms of quality. Hughes paid, in the 1930s and through the 40s and early 50s, for his once deep attachment to radical socialism; Ellison quietly shed similar attachments in the name of a complex patriotism. In doing so, he escaped the rough treatment meted out to Hughes and others. Jackie Robinson was by far the most famous of the three, and no doubt had the greatest impact, as a force for desegregation, on American culture. While he was not an artist or intellectual, he was drawn to politics especially after the end of his baseball career. He was a moderate Republican; the others were Democrats, although Hughes was more critical of party politics than was Ellison, who was befriended and advanced by President Johnson. Both Johnson and, later, Ronald Reagan awarded Ellison the prestigious Presidential Medal of the Arts. Amazon.com: Invisible Man is one of only a few novels from its era that has kept its power and popularity for readers in later generations. Has it had a similar influence on younger writers? Ellison's prickly relations with his successors may have discouraged immediate followers, but can you see his influence today? Rampersad: Young writers today, black as well as white, have many sources to draw on and many beacons of inspiration to guide them. And yet Invisible Man is in many ways as admirable, fascinating, and complex today as when it was first published. Among novels by black Americans, its only true rival in terms of quality of craft might be Morrison's Beloved, and the wide range of effects in Ellison's novel is probably unmatched by any other black novelist. Ellison, we should remember, set out consciously to write a novel that was simultaneously about a black man and about an Everyman who transcended race, and to a surprising extent he succeeded in doing so. His novel continues to appeal to blacks and whites alike, and especially to men. Moreover, in writing so brilliantly about race, which remains and probably will remain the most challenging topic in American culture, he practically guaranteed the continuing resonance of Invisible Man. The superiority of Shadow and Act, his 1964 collection of essays and interviews, to virtually every other book on the subject of black art and culture is evident. Its only serious rival in this respect is probably Du Bois's The Souls of Black Folk (1903). But Shadow and Act lives while much, although not all, of Du Bois's classic book is dated. Shadow and Act continues to serve as a primer for younger black writers who are seriously interested in questions of literary craft and race in America. |

| Other Award Winning Books by Arnold Rampersad |

|

|

| Arnold Rampersad Award Stats |

|

| *Major Prize = Pulitzer Prize, National Book Critics Circle Award, National Book Award, Man Booker Prize, and PEN/Faulkner Award |

Rampersad: Ellison, who spent the first 20 years of his life in Oklahoma, was intensely aware of the pioneers, white and black, who had migrated toward the end of the 19th century, from the South especially, into what had been demarcated as "Indian" territory. These pioneers had come first as homesteaders, then as founders of the state of Oklahoma in 1907, six years before Ralph's birth. For the rest of his life he carried with him a keen, precious sense of Oklahoma as an extraordinary American site, one that captured much of the complexity of America as it had been shaped by frontier life. Oklahoma City meant excellent jazz and the blues--black culture in its artistic exuberance--as in the pioneering jazz guitarist Charlie Christian (who played later with Benny Goodman) and the equally famous blues singer Jimmie Rushing. But Ellison also knew Oklahoma as a place where Jim Crow was a disturbing, often ruinous force. Moreover, his father had died there when Ralph was only three, and the result was that his mother was forced to toil in humble jobs that sorely embarrassed a proud boy.

Rampersad: Ellison, who spent the first 20 years of his life in Oklahoma, was intensely aware of the pioneers, white and black, who had migrated toward the end of the 19th century, from the South especially, into what had been demarcated as "Indian" territory. These pioneers had come first as homesteaders, then as founders of the state of Oklahoma in 1907, six years before Ralph's birth. For the rest of his life he carried with him a keen, precious sense of Oklahoma as an extraordinary American site, one that captured much of the complexity of America as it had been shaped by frontier life. Oklahoma City meant excellent jazz and the blues--black culture in its artistic exuberance--as in the pioneering jazz guitarist Charlie Christian (who played later with Benny Goodman) and the equally famous blues singer Jimmie Rushing. But Ellison also knew Oklahoma as a place where Jim Crow was a disturbing, often ruinous force. Moreover, his father had died there when Ralph was only three, and the result was that his mother was forced to toil in humble jobs that sorely embarrassed a proud boy.